Management of food and feed safety crises in the EU follows a new master plan – effective 13.3.19 – following special decision 19.2.19 of the European Commission. (1)

Food security and crisis management, the issues to be addressed

The ineffectiveness of the apparatus in charge of handling emergencies on food and feed is hinted at in the introduction of the Brussels document. Only one of many examples of poorly managed crises, mostly related to food fraud, is captured. (2) The ‘Fipronil case,’ the acaricide that contaminated eggs from Belgium and several other countries, then spread to every Internal Market territory in summer 2017. (3)

The Commission led by Vytenis Andriukaitis, predictably, lacks the intellectual honesty needed to acknowledge their mistakes. Neither does it mention the most serious of security crises ever even managed, for unacceptable subservience to Big Food., with malicious omission of dutiful and urgent official acts. Namely, the overt chemical contamination of most foods with palm oil

– including milk replacer formulas for infants

and foods intended for children

– with genotoxic and carcinogenic substances.

Responsibilities are thus shifted to member states and research laboratories and centers. With the hypocrisy of not distinguishing between omertous and inefficient governments-Germany, the United Kingdom, Belgium and the Netherlands ‘in primis‘-and virtuous ones such as Italy, which has always been first in the number of alerts in the alert system. It is no coincidence that our country, thanks to a system of official public controls to which unparalleled resources are devoted and its coordination by the Ministry of Health, has been marginally involved in the serious pan-European incidents, from BSE to the present. (4)

Coordination between (some) governments and the European Commission has often been deficient and late, risk communication inconsistent and uneven. Even earlier and even worse, risk assessment has recorded differing positions with discouraging outcomes for citizens and consumers, who have lost confidence in the entire food chain and those who are called upon to control it. Causing inestimable damage to entire supply chains, such as the poultry industry in the case of avian flu, and reactions of serious distrust with respect to existing procedures (regarding, for example, the renewal of glyphosate authorization). (5)

Crisis management, goals of the new EC plan

Decision 300/2019 updates the European Commission’s master plan to address situations where there is an occurrence or well-founded fear of (direct or indirect) public health risks related to food and feed. Brussels recognizes the need for a series of interventions based on the experiences-predominantly negative, as mentioned above-over the years. Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen, modify and point out what was established at the time in the previous Commission decision that has since been repealed. (6)

‘

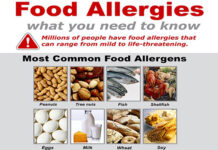

Public health hazards

can be biological, chemical, and physical in nature and include hazards related to radioactivity and

allergens

. However, the general plan’s approach, principles and practical procedures could also be considered as guidelines for the management of other foodborne incidents that do not pose the above public health risks.‘ (EC Decision 2019/300, Recital 8)

The main objective of the new EU food and feed safety crisis management master plan is to protect public health. The ambition is to ensure an adequate level of preparedness of the authorities (national and European) in charge of assessing and managing the and incidents related to physical, chemical and microbiological contamination, as well as radioactivity, on foodstuffs destined for ‘food and feed‘ chains.

Food security crisis management in EU, the 3 key concepts

The new master plan for managing possible emergencies related to food and feed health risks is based on three key concepts. Graduality, coordination of actions, communication strategy.

1) Graduality

The master plan is activated when interim emergency measures taken by member states and/or the Commission itself are not sufficient to prevent, reduce or eliminate the risk to human health. (7) Two levels of intervention are provided:

– Enhanced coordination (Art. 10) or, in the most serious cases,

– The establishment of a crisis unit (Art. 12).

Risk classification is essential and must be timely. Given the nature, severity, and foreseeable magnitude of the incident, but also political and consumer sensitivities. This requires ongoing monitoring, data collection and analysis, training and regular meetings between coordinators and national points of contact.

2) Coordination

Coordination between member states and the Commission, like that between alert systems and laboratories, must ensure a rapid response to the onset of an emergency so that effective strategies can be developed. Therefore, the link between EWRS (Rapid Alert and Response System) and RASFF (Rapid Alert System on Food, Feed and Contact Materials) is strengthened, in the ‘One Health’ logic.

The Commission is responsible for coordinating the necessary actions and is assisted by state coordinators, members of the crisis unit as well as and responsible at the national level for coordinating food and feed crises and managing the communication strategy (Articles 18, 19).

3) Communication and transparency

Transparency and communication strategy are the two essentials to crisis management. Information must be accurate, well-founded, consistent, relevant, and timely. Peculiar attention should be paid to the consumer, whose trust in the system is crucial to the extent that the system itself proves reliable. (8)

The news flow should then be managed by the Commission in synergy and harmony with the state coordinators (as never before). In line with European scientific agencies (Efsa, Ecdc) and international networks (Infosan).

Dario Dongo and Marina De Nobili

Notes

(1) Dec. EC 2019/300

, ‘

Establishing a general plan for crisis management concerning food and feed safety’

, on

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/IT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019D0300&from=IT

(2) At the same time as the Fipronil case, a crisis of quite different severity emerged, over German and Dutch pork contaminated with Hepatitis E, which has instead remained under wraps. A few months the global Brazilian meat scandal, ‘

Carne Fraca

‘

. A few years earlier the chilling ”

Horsegate

‘

which involved the entire membership of

Big Food

. Not forgetting ITX, a hazardous substance migrated into Nestlé infant milk, nor the more recent cases. From frozen Hungarian peas to Listeria To salmonella in Lactalis early childhood foods.

(3) On the Fipronil case we refer to previous writings and reflections, on https://www.greatitalianfoodtrade.it/idee/uova-al-fipronil-riflessioni-sull-ennesima-frode-alimentare-in-europa, https://www.greatitalianfoodtrade.it/etichette/bollino-fipronil-free-sulle-uova-magari-no, https://www.greatitalianfoodtrade.it/salute/fipronil-prima-riunione-a-bruxelles, https://www.greatitalianfoodtrade.it/salute/fipronil-prima-riunione-a-bruxelles

(4) For further discussion on the topic, with comparisons of current rules in the EU and those adopted in the US and China, please refer to our free ebook ‘

Food safety, mandatory rules and voluntary standards

‘, at

https://www.greatitalianfoodtrade.it/libri/sicurezza-alimentare-regole-cogenti-e-norme-volontarie-il-nuovo-libro-di-dario-dongo

. The serious weaknesses of the current crisis management system in the US and Canada are highlighted in the previous article https://www.greatitalianfoodtrade.it/mercati/usa-e-canada-sotto-silenzio-il-più-grande-richiamo-del-2018

(5) Do not forget the underestimation by the German Risk Assessment Authority (BfR) back in 2011 of the serious public health hazards of glyphosate exposure. See the article https://www.greatitalianfoodtrade.it/idee/armi-di-distruzione-di-massa-il-glifosato

(6) See Decision 2004/478/EC, repealed by the one under review. Both decisions were made under reg. EC 178/02, Article 55

(7) See reg. EC 178/02, Articles 53, 54

(8) Germany’s disastrous handling of the E.Coli emergency in sprouts in 2011 cost the EU 277 million euros (to restore consumer confidence in Mediterranean cucumbers and tomatoes, innocent victims of Teutonic misinformation). And it was the third German-generated crisis in 12 months, in 2011-2012, after ol

bacillus cereus

in mozzarella cheese and dioxins in animal feed (see.

https://ilfattoalimentare.it/germania-lo-scandalo-diossina-dilaga-a-macchia-dolio-lacune-e-ritardi-nei-controlli.html

)