Recent press reports make erythritol appear to be a dangerous ingredient. At the origin of the alarmism is a publication that appeared in February 2023 in the journal Nature Medicine, titled‘The artificial sweetener erythritol and cardiovascular event risk,’ (1) in which the widespread sweetener, used abundantly both as an ingredient and in ketogenic diets, is accused of being responsible for heart attacks.

Before we throw out all the erythritol stored at home, let’s take a closer look at the article and then explain how this study was carried out and what limitations it highlights.

What is erythritol?

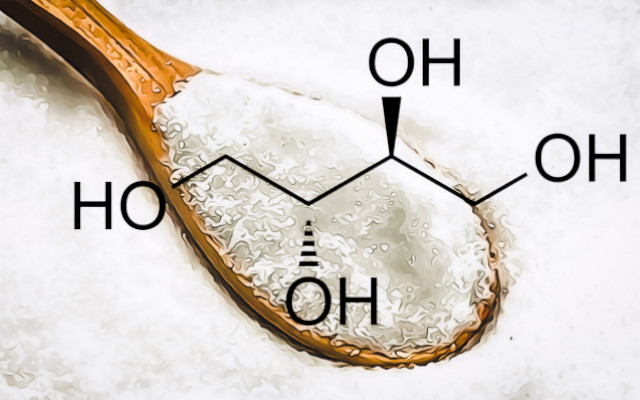

Erythritol is a four-carbon-atom polyol (formula C4H10O4) found naturally in fruits, vegetables as well as fermented foods and beverages. (2)

Because of its zero caloric value and negligible glycemic and insulinemic index, it has long been used as a viable sugar substitute.

Widely studied from a toxicological and safety perspective, erythritol is generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (3) as well as in Europe for its intended use in food (4).

The study in Nature Medicine

The study published in Nature Medicine from the title describes erythritol as an ‘artificial’ sweetener, insisting on this point throughout the article. This approach almost makes it seem as if there is an intention from the outset to want to equate polyols obtained from fruit fermentation and totally artificial intensive sweeteners (e.g., “I’m not going to use any artificial sweeteners”) with totally artificial sweeteners (e.g., “I’m not going to use any artificial sweeteners”). aspartame, neotame, acesulfame K, etc.).

Moving on in their discussion, the authors begin to argue for their even more negative portrayal of erythritol, citing as an example a small prospective study done on some college freshmen in which they correlated blood erythritol levels with increased body weight. (5)

But the Nature study points to something even more dangerous:‘results confirm that circulating levels of erythritol are associated with the risk of adverse cardiovascular events, independent of traditional CVD (Cardio Vascular Disease) risk factors.’

The goal of the research

The goal of the research was to find a correlation between unknown chemicals or compounds in the blood and subjects who might have the risk of heart attack, stroke, or death in the next three years. To do this, the team analyzed 1,157 blood samples, collected between 2004 and 2011, in subjects at risk for heart disease. (6)

To confirm the results, the team of researchers tested another set of blood samples from more than 2,100 people in the United States and another 833 samples collected by colleagues in Europe through 2018 (7). It is important to note that about three quarters of the

participants, in all three populations, had coronary heart disease or high blood pressure, and about one-fifth had diabetes. More than 50% were male subjects between 60 and 70 years old.

Continuing in the study, the researchers found that, in the three populations, higher levels of erythritol were correlated with a higher risk of heart attack, stroke, or death within the next 3 years.

8 healthy volunteers

In the final part, the study wanted to examine eight healthy volunteers (yes, as many as eight volunteers over eight years of study) who were given a drink containing 30 grams of erythritol. The amount, according to the researchers (who, however, do not indicate the source of this data), contained in one pint (about half a liter) of ketogenic ice cream.

Two values were monitored in them: blood levels (millimolar) of erythritol and clotting risk. The results state that 30 grams of erythritol caused blood levels of erythritol to rise 1,000-fold, remaining elevated for the next two to three days and above the threshold needed to trigger and increase the risk of clotting. In support of this, the authors report that, in vitro, the addition of erythritol to a platelet-rich blood plasma increases platelet aggregation in response to ADP (adenosine diphosphate).

By constructing the study in this way, the team of researchers had essentially all the elements for an extremely viral article title, on a highly topical subject, as there is much talk about reducing sugar in the diet and replacing it with sweeteners.

On this note, at the end of the article, we also read that many observational epidemiological studies report that the use of artificial sweeteners is associated with various adverse health outcomes, including mortality from cardiovascular disease, but without specifying in any way which artificial sweeteners these are (8). Given that strictly speaking science should undoubtedly be provided. A missing data therefore, and of a fundamental nature, since within the category ‘artificial sweeteners’ we find a great variability of molecules that are very different from each other and above all from the ways of use (quantities, mixtures…) that differ from each other.

The limitations of the study

The first consideration to be made regarding the limitations of publication is related to the type of study conducted. This is correlational research, so this means that it is not based on the fundamental principle of cause-and-effect.

This type of research focuses solely on finding and correlating observations in variable Y, observing and recording variable X (see the in-depth discussion on correlational studies at the end of the article).

The dangerous allure of correlational studies

Taking a practical example, an excellent correlation between per capita margarine consumption (cause) and divorce rate (effect) in the state of Maine over 10 long years can be seen in the graph below. Incredibly, the two curves are identical.

By its elementary (and paradoxical if you will) nature, this correlation allows everyone to understand in an obvious way that there can be no relationship between cause and effect.

To be credible, a correlational study must necessarily be accompanied by a cause-and-effect experimental study in which manipulating one variable (cause) measures the direct, correlated effect on the second variable (effect). If this is not done, it will be easy to fascinate readers with correlations that seem convincing but then in practice if the actual cause-and-effect correlation is not provided the study is likely to be misleading at the very least. The example of the correlation between divorce and margarine consumption in Maine is the most illuminating example.

How to stay in the ‘scientific security’ zone

The research authors themselves construct the article with a very effective ‘narrative’ architecture:

1) the initial part (title included) steeped in negativity about sweeteners,

2) the next part devoted to describing the interesting and simple correlational study,

3) the final scientifically unimpeachable part, where they finally declare the absence of the cause-and-effect study, stating that, based on the design put in place, this study can only show an association and not causality, finally acknowledging the possibility of unmodeled confounding (e.g., diet) that might have directly or indirectly influenced the results by factors that were not included in their experimental models at all.

The limitations stated by the researchers themselves

Since the enrolled patients already showed a high prevalence of cardiovascular disease and traditional risk factors, moreover, it is not realistically possible to determine the translatability of the results to the general population.

Limitations to the interpretation of measurements made in vitro are also noted in the study. Historically, measurements of platelet function in vitro are used to demonstrate the effects of drugs that inhibit function rather than improve it. This study did not measure platelet function in the blood of subjects following erythritol consumption. In fact, the authors extrapolated data from their in vitro measurements to predict effects based on blood levels of erythritol following consumption of the sweetener in a different group of subjects.

The results of this study would have been more convincing if measurements of platelet function had been made on platelets from subjects after erythritol vs placebo consumption, or better yet by measuring the number of activated circulating platelets by flow cytometry. And even that has not been done.

Cause or effect

The limit most underestimated is perhaps that erythritol (which the authors point to as an artificial sweetener) is endogenously synthesized from glucose via the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) and that high blood erythritol levels have been shown to be caused by high glucose levels and oxidative stress (which happens in virtually all individuals with disrupted glucose metabolism!), two key factors in the pathogenesis of cardiometabolic diseases [9]. In other words, it is the high levels of glucose and oxidative stress that are related to CVD, while circulating erythritol is only a consequence of them.

Dr. Oliver Jones, professor of chemistry at RMIT University of Victoria in Australia, said that any possible (as yet unproven) risk of excess erythritol levels should also be balanced against the real health risks of excessive glucose consumption and argued that ‘because the people in the study already had many cardiovascular risk factors, it cannot be shown that it is not one of these other factors that causes an increased risk of clotting‘. [8]

That is why the study carried out in this way cannot possibly indicate the cause-and-effect correlation.

Research on erythritol

Erythritol has been a studied ingredient since 1935. Since that date, there have been so many scientific publications done by so many universities and research groups worldwide on its use and the beneficial effects found by using it in the diet.

More exactly, there are more than 2,500 articles published in scientific journals of different nationality, cut and authority. Having specified this, there are several researches on erythritol and its beneficial effects, including.

- erythritol has been shown not to affect glucose and insulin concentrations and appears to have protective effects on endothelial function in patients with DMT2, (10, 11, 12)

- A study conducted on 24 type 2 diabetics consuming 36 grams of erythritol daily for 4 weeks concludes that ”Acute erythritol improved endothelial function as measured by peripheral arterial fingertip tonometry. Chronic erythritol reduced central pulse pressure and tended to decrease carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity. Therefore, erythritol consumption markedly improved small vessel endothelial function and chronic treatment reduced central aortic stiffness’. In other words, it improved blood pressure which helps reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, (13)

- a recent study has shown that ghrelin concentrations are suppressed following oral administration of erythritol in healthy subjects, (14)

- A pilot study documented that acute ingestion of erythritol does not affect blood lipid or uric acid concentrations, (15)

- erythritol may also have other beneficial effects, for example, it may act as an antioxidant [16] and may improve dental health in humans. (17)

Having said that, having analyzed how the study was conducted and observing how many publications still point to this natural ingredient as the best answer to sugar (and its harms proven by science), it seems especially necessary to point out the difference between correlation and causation and the difference between endogenous versus exogenous levels of erythritol in healthy individuals or those at risk of cardiovascular disease.

P.S. What is a correlational study?

A correlational study is a type of scientific research that examines the relationship between two or more variables without manipulating them in any way. In a correlational study, researchers collect data on two or more variables and use statistical techniques to determine whether there is a relationship between them.

For example, a researcher might conduct a correlational study to examine the relationship between age and blood pressure. In this case, the researcher would collect data on a group of people, recording their age and blood pressure, and then use statistical techniques to determine whether there is a relationship between these two variables.

A correlational study can be useful in identifying relationships between variables, but it cannot establish cause and effect between them. Therefore, if researchers want to determine whether one variable causes the other, they should conduct an experimental study in which they manipulate one variable (cause) and measure the effect on the second variable (effect).

Gianluca Baccheschi

Bibliography

(1) Witkowski, M., Nemet, I., Alamri, H. et al. The artificial sweetener erythritol and cardiovascular event risk. Nat Med 29, 710-718 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02223-9

(2) Suitability of sugar alcohols as antidiabetic supplements: A review. Nontokozo Z. Msomi et Al. J Food Drug Anal. 2021; 29(1): 1-14.

(3) GRN No. 789 Erythritol: https://www.cfsanappsexternal.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/index.cfm?set=GRASNotices&id=789

(4) Commission Regulation (EU) 2015/1832 of October 12, 2015: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/IT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32015R1832&from=SL

(5) Erythritol is a pentose-phosphate pathway metabolite and associated with adiposity gain in young adults, Katie C. Hootman et Al. PNAS May 8, 2017 114 (21) E4233-E4240

(6) clinicaltrials.com: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00590200

(7) clinicaltrials.com: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00590200

(8) Dietamecicale.co.uk/depths: https://www.dietamedicale.it/approfondimenti/il-dolcificante-eritritolo-e-il-rischio-di-patologie-cardiovascolari-un-approccio-scientifico; 02/03/2023

(9) Regulation of Erythritol Metabolism, a Biomarker of Cardiometabolic Disease. Semira Ortiz and Martha Field Current Developments in Nutrition, Volume 5, Supplement 2, June 2021, 5140515

(10) Gut hormone secretion, gastric emptying, and glycemic responses to erythritol and xylitol in lean and obese subjects. Bettina K. Wölnerhanssen et Al. American Journal of Physiology, 14 JUN 2016 https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00037.2016

(11) Gastric emptying of solutions containing the natural sweetener erythritol and effects on gut hormone secretion in humans: A pilot dose-ranging study. Bettina K. Wölnerhanssen MD et Al, Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism February 10, 2021 https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.14342

(12) Effects of Oral Administration of Erythritol on Patients with Diabetes. Masashi Ishikawa et Al. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, Volume 24, Issue 2, October 1996, Pages S303-S308

(13) Effects of erythritol on endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a pilot study. Nir Flint et Al. Acta Diabetologica volume 51, pages 513-516 (2014)

(14) An Erythritol-Sweetened Beverage Induces Satiety and Suppresses Ghrelin Compared to Aspartame in Healthy Non-Obese Subjects: A Pilot Study. Zachary A Sorrentino et Al. Cureus. 2020 Nov; 12(11): e11409.

(15) Gastric emptying of solutions containing the natural sweetener erythritol and effects on gut hormone secretion in humans: A pilot dose-ranging study. Bettina K. Wölnerhanssen MD et Al. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, February 10, 2021 https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.14342

(16) Erythritol is a sweet antioxidant. Gertjan J.M. den Hartog Ph.D. et Al. Nutrition, Volume 26, Issue 4, April 2010, Pages 449-458

(17) Effect of Erythritol and Xylitol on Dental Caries Prevention in Children. Honkala S. et Al. Caries Res 2014; 48: 482-490

Professional journalist since January 1995, he has worked for newspapers (Il Messaggero, Paese Sera, La Stampa) and periodicals (NumeroUno, Il Salvagente). She is the author of journalistic surveys on food, she has published the book "Reading labels to know what we eat".