Microalgae represent a promising source of sustainable lipids, offering significant advantages over conventional terrestrial oil crops through their high area-specific productivity, capacity to grow on non-arable land, and efficient nutrient utilisation (Barbosa et al., 2023).

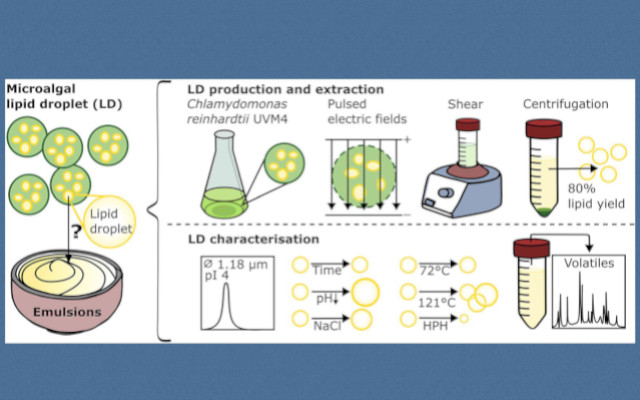

A recent study by Baumgartner et al. (2025) from the Institute of Food, Nutrition and Health, Sustainable Food Processing Group, ETH Zurich, published in Food Hydrocolloids, explores the potential of lipid droplets (LDs) extracted from the microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii as natural food emulsifiers.

Unlike traditional microalgal oil production, which requires energy-intensive drying and organic solvent extraction, the direct use of pre-emulsified LDs could offer a more sustainable approach to lipid utilisation whilst circumventing the need for re-emulsification processes.

Methodology

The research employed cell wall-deficient C. reinhardtii UVM4 cultivated phototrophically under nitrogen limitation to induce lipid accumulation. Cell disruption was achieved using pulsed electric fields (PEF) treatment with electric field strengths of 11.8–14.7 kVcm⁻¹ and volumetric energy inputs of 21.9–28.2 kJ L⁻¹ (Baumgartner et al., 2025). Following PEF treatment, LDs were extracted aquously with 10 wt% glucose supplementation to facilitate separation during centrifugation at 3,000×g for 30 minutes. Both crude and purified LD extracts were characterised using laser diffraction particle size analysis, ζ-potential measurements, optical microscopy, and SDS-PAGE protein profiling.

The study systematically evaluated LD stability under various conditions relevant to food processing applications. Physical stability was assessed across pH ranges (2–6.5), sodium chloride concentrations (0–3.5 M), thermal treatments (pasteurisation at 72°C for 21 seconds and sterilisation at 121°C for 20 minutes), high-pressure homogenisation (110 MPa), and freeze-thaw cycling. Chemical stability was examined through headspace volatile analysis to identify oxidation products, particularly aldehydes associated with lipid degradation.

Major outcomes

The aqueous extraction method achieved an impressive lipid recovery of 81 ± 1 wt%, approaching yields reported for seed-derived LDs such as rapeseed (90 wt%) and sunflower (87 wt%) (Romero-Guzmán et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2023). Crude LD extracts contained 2.7 ± 0.9 g L⁻¹ lipids and 0.26 ± 0.02 g L⁻¹ proteins, whilst purified extracts comprised 96.4 ± 1.0 wt% lipids and 3.6 ± 1.0 wt% proteins. Protein profiling revealed a prominent band between 25 and 35 kDa, likely corresponding to the major lipid droplet protein (MLDP), consistent with previous findings (Moellering & Benning, 2010; Nguyen et al., 2011). The volumetric mean diameter D[4,3] of crude LDs was 1.78 ± 0.08 μm.

Stability testing demonstrated that pH significantly influenced LD behaviour. The isoelectric point was determined to be pH 4, lower than the pH 5.7–6.6 range reported for seed-derived LDs (Tzen et al., 1993). Remarkably, LDs coalesced at their isoelectric point, contrasting with the behaviour of seed-derived LDs that remain sterically stabilised by oleosins even at their pI (Tzen & Huang, 1992). Nevertheless, LD size distributions remained largely stable over 2–4 weeks of storage at 4°C at neutral pH, with only minor peaks appearing at 20–40 μm.

Thermal processing had differential effects on LD integrity. Pasteurisation (72°C for 21 seconds) caused only slight increases in larger droplets (3–7 μm), whilst sterilisation (121°C for 20 minutes) induced pronounced aggregation and coalescence comparable to that observed after freeze-thawing. High-pressure homogenisation successfully reduced the Sauter mean diameter D[3,2] from 1.16 ± 0.13 μm to 0.74 ± 0.02 μm (p = 0.0007), indicating that co-extracted proteins effectively stabilised the increased interfacial area.

Discussion

The study provides compelling evidence that electrostatic repulsion serves as the primary stabilisation mechanism for C. reinhardtii LDs, as evidenced by pH-dependent coalescence and ζ-potential measurements. The lower isoelectric point compared to seed-derived LDs presents a practical advantage, enabling stability across a broader pH range relevant for acidic food products. However, the coalescence observed at the pI suggests that steric stabilisation by MLDP may be weaker than that provided by oleosins in seed LDs (Chapman et al., 2012). This difference likely stems from the absence of structural similarity between MLDP and oleosins (Davidi et al., 2012).

A critical limitation identified was lipid oxidation initiated during cell disruption rather than storage. Volatile analysis revealed hexanal and other aldehydes as dominant compounds immediately post-extraction, indicating enzymatic lipid peroxidation catalysed by released pigments, metals, and reactive oxygen species (Schaich et al., 2012). Notably, pasteurisation significantly increased aldehyde content (p = 1.15×10⁻¹²), possibly due to faster inactivation of lipolytic enzyme inhibitors relative to the enzymes themselves (Prado et al., 2006). This oxidative instability poses challenges for preserving polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), a key nutritional advantage of microalgal lipids.

The freeze-thaw instability observed contrasts with the partial resistance reported for seed-derived LDs (Nikiforidis et al., 2011), though some C. reinhardtii LDs retained structural integrity, suggesting heterogeneous interfacial protein coverage (Tsai et al., 2015). Similarly, elevated NaCl concentrations (up to 3.5 M) induced less pronounced coalescence than pH alterations, indicating that charge shielding alone is insufficient to destabilise LDs as effectively as direct surface charge modifications.

EU novel food assessment of C. reinhardtii

The microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (specifically the dried biomass powder of strain THN 6) was submitted for authorisation under Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 on novel foods in the European Union.

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) issued a scientific opinion on 30 April 2025 in which it concluded that the safety of the novel food could not be established, owing to significant data gaps regarding identity, production process, composition, history of use, proposed uses, genotoxicity and allergenicity.

Since then, the European Commission implemented a decision on 10 September 2025 terminating the authorisation procedure for this application without updating the Union list of authorised novel foods. Consequently, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii remains not authorised for placing on the EU market as a novel food.

Our FARE (Food and Agriculture Requirements) unit at Wiise Benefit supports companies and research consortia in designing studies and in preparing and submitting dossiers for novel food authorisations. Our expertise in the regulatory analysis of microalgae and the blue bioeconomy, demonstrated through the ProFuture research project, enables us to provide robust and highly specialised assistance.

Perspectives for the food industry

The potential application of microalgal lipid droplets as natural emulsifiers presents compelling opportunities for the food industry, particularly as alternatives to synthetic emulsifiers such as lecithin, mono- and diglycerides, and polysorbates. The growing consumer demand for clean-label products and plant-based alternatives has intensified the search for natural emulsification systems that can replace chemically modified ingredients whilst maintaining product stability and functionality (McClements et al., 2019). Microalgal LDs could address this need in multiple applications, including plant-based milk alternatives, salad dressings, mayonnaise, and dairy-free spreads, where their pre-emulsified nature eliminates the requirement for additional emulsification steps or synthetic stabilisers.

Unlike conventional emulsifiers derived from soy or egg lecithin, the LDs from C. reinhardtii do not raise allergenicity concerns. Moreover, they benefit from GRAS status in the United States and have obtained novel food approval in certain jurisdictions (Wei, 2022). Furthermore, the inherent nutritional value of microalgal lipids, particularly their polyunsaturated fatty acid content, positions these natural emulsions as functional ingredients that contribute both technological and health benefits. However, realising this potential will require addressing oxidative stability challenges and developing cost-effective production methods that can compete with established emulsifier markets. Commercialisation could therefore initially focus on premium-segment products, where sustainability credentials and nutritional functionality can justify the higher costs.

Conclusions

This comprehensive investigation demonstrates that microalgal lipid droplets from C. reinhardtii represent a viable platform for developing additive-free natural emulsions with reduced land and fertiliser requirements compared to terrestrial crops (Baumgartner et al., 2025). The successful extraction using solvent-free methods, combined with stability during pasteurisation and homogenisation, positions these LDs favourably for food applications. The broader pH stability range relative to seed-derived LDs offers particular advantages for acidic food formulations.

However, significant challenges remain, particularly regarding oxidative stability during extraction. Future research should prioritise developing process strategies to suppress enzymatic oxidation, such as thermal conditioning prior to cell disruption (Rasor & Duncan, 2014), and systematic quantitative oxidation assessment. The relatively low LD concentrations achieved (2.7 g L⁻¹ lipids in crude extracts) necessitate optimisation for industrial-scale applications. Given the higher production costs of microalgal lipids compared to seed-derived alternatives (Benvenuti et al., 2017), high-value applications such as PUFA fortification appear most promising.

The findings highlight fundamental differences in stabilisation mechanisms between microalgal and seed LDs, attributed to distinct proteome and glycerolipid compositions. Whilst C. reinhardtii LDs lack the robust steric stabilisation conferred by oleosins, their unique properties may offer advantages in specific applications. Further investigations into LD surface composition and species-specific variations, particularly in microalgae with different dominant LD proteins such as Nannochloropsis oceanica (Goold et al., 2015), will be essential to fully realise the potential of microalgal LDs as sustainable, functional ingredients for food, biotechnological, and cosmetic industries.

Dario Dongo

Cover image: Baumgartner et al. (2025), graphical abstract

References

- Barbosa, M. J., Wijffels, R. H., Janssen, M., Südfeld, C., & Adamo, S. D. (2023). Hypes, hopes, and the way forward for microalgal biotechnology. Trends in Biotechnology, 41(3), 452–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2022.12.017

- Baumgartner, J., Arita-Merino, N., Schwager, N., Spahn, D., Ambrosioni, M., Thaler, S., Radiom, M., Boulos, S., Dumpler, J., Fischer, P., & Mathys, A. (2025). The potential of lipid droplets from the microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii as natural emulsions. Food Hydrocolloids, 172, 112114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2025.112114

- Baumgartner, J., Chua, S. T., Blunier, M., Gao, F., Arita-Merino, N., Abiusi, F., Archer, L., Cybulski, K., Smith, A. G., Studer, M. H., & Mathys, A. (2025). Comparison of lipid droplet extraction from cell wall-deficient Chlamydomonas reinhardtii with pulsed electric fields or osmotic shock. Bioresource Technology, 434, 132764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2025.132764

- Benvenuti, G., Ruiz, J., Lamers, P. P., Bosma, R., Wijffels, R. H., & Barbosa, M. J. (2017). Towards microalgal triglycerides in the commodity markets. Biotechnology for Biofuels, 10(1), 188. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-017-0873-2

- Chapman, K. D., Dyer, J. M., & Mullen, R. T. (2012). Biogenesis and functions of lipid droplets in plants: Thematic review series: Lipid droplet synthesis and metabolism: From yeast to man. Journal of Lipid Research, 53(2), 215–226. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R021436

- Davidi, L., Katz, A., & Pick, U. (2012). Characterization of major lipid droplet proteins from Dunaliella. Planta, 236(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-011-1585-7

- European Commission. (2025, September 10). Commission Implementing Decision terminating the procedure for authorisation of dried biomass powder of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii THN 6 as a novel food without updating the Union list of novel foods (C(2025) 5980 final).

- European Food Safety Authority. (2025, April 30). Safety of dried biomass powder of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii THN 6 as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA Journal, 23(4), e9413. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2025.9413

- Goold, H., Beisson, F., Peltier, G., & Li-Beisson, Y. (2015). Microalgal lipid droplets: Composition, diversity, biogenesis and functions. Plant Cell Reports, 34(4), 545–555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00299-014-1711-7

- McClements, D. J., Newman, E., & McClements, I. F. (2019). Plant-based milks: A review of the science underpinning their design, fabrication, and performance. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 18(6), 2047–2067. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12505

- Moellering, E. R., & Benning, C. (2010). RNA interference silencing of a major lipid droplet protein affects lipid droplet size in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Eukaryotic Cell, 9(1), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1128/EC.00203-09

- Nguyen, H. M., Baudet, M., Cuiné, S., Adriano, J. M., Barthe, D., Billon, E., Bruley, C., Beisson, F., Peltier, G., Ferro, M., & Li-Beisson, Y. (2011). Proteomic profiling of oil bodies isolated from the unicellular green microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: With focus on proteins involved in lipid metabolism. Proteomics, 11(21), 4266–4273. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmic.201100114

- Nikiforidis, C. V., Karkani, O. A., & Kiosseoglou, V. (2011). Exploitation of maize germ for the preparation of a stable oil-body nanoemulsion using a combined aqueous extraction-ultrafiltration method. Food Hydrocolloids, 25(5), 1122–1127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2010.10.009

- Prado, B. M., Sombers, S. E., Ismail, B., & Hayes, K. D. (2006). Effect of heat treatment on the activity of inhibitors of plasmin and plasminogen activators in milk. International Dairy Journal, 16(6), 593–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idairyj.2005.09.018

- Rasor, A. S., & Duncan, S. E. (2014). Fats and oils – Plant based. In S. Clark, S. Jung, & B. Lamsal (Eds.), Food processing: Principles and applications (2nd ed., pp. 457–480). John Wiley & Sons.

- Romero-Guzmán, M. J., Jung, L., Kyriakopoulou, K., Boom, R. M., & Nikiforidis, C. V. (2020). Efficient single-step rapeseed oleosome extraction using twin-screw press. Journal of Food Engineering, 276, 109890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2019.109890

- Schaich, K. M., Shahidi, F., Zhong, Y., & Eskin, N. A. M. (2012). Lipid oxidation. In N. A. M. Eskin, & F. Shahidi (Eds.), Biochemistry of foods (pp. 419–469). Academic Press Elsevier.

- Tsai, C. H., Zienkiewicz, K., Amstutz, C. L., Brink, B. G., Warakanont, J., Roston, R., & Benning, C. (2015). Dynamics of protein and polar lipid recruitment during lipid droplet assembly in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. The Plant Journal, 83(4), 650–660. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.12917

- Tzen, J. T. C., Cao, Y. Z., Laurent, P., Ratnayake, C., & Huang, A. H. C. (1993). Lipids, proteins, and structure of seed oil bodies from diverse species. Plant Physiology, 101(1), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.101.1.267

- Tzen, J. T. C., & Huang, A. H. C. (1992). Surface structure and properties of plant seed oil bodies. Journal of Cell Biology, 117(2), 327–335. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.117.2.327

- Wei, S. (2022). NHC approved 3 new food raw materials and 18 new food additives in China. CIRS. Retrieved from https://www.cirs-group.com/en/food/nhc-approved-3-new-food-raw-materials-and-18-new-food-additives-in-china

- Yang, J., Vardar, U. S., Boom, R. M., Bitter, J. H., & Nikiforidis, C. V. (2023). Extraction of oleosome and protein mixtures from sunflower seeds. Food Hydrocolloids, 145, 109078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.109078

Dario Dongo, lawyer and journalist, PhD in international food law, founder of WIISE (FARE - GIFT - Food Times) and Égalité.