The global food security crisis, affecting more than 735 million people in 2023 (SOFI report, 2024), intersects critically with the environmental burden of conventional textile production. A groundbreaking study by Allen et al. (2025) demonstrates how bio manufacturing protein fibres through fermentation processes can address both challenges simultaneously. Traditional plant-based fibres such as cotton require substantial resources, with one kilogram of cotton demanding approximately 10,000 litres of water and occupying 32 million hectares globally (Allen et al., 2025).

By leveraging yeast biomass through enzymatic processing and lyocell-based spinning techniques, this research presents a viable alternative that decouples textile production from agricultural land, thereby freeing resources for food cultivation.

The study builds upon historical interest in regenerated protein fibres, which dates to the nineteenth century with early gelatin-based materials and subsequent innovations such as Lanital from milk casein in 1936. However, commercial production of such fibres declined by the mid-1960s due to competition from cheaper synthetic alternatives with superior mechanical properties (Allen et al., 2025; Brooks, 2009). Recent advances in fermentation technology have renewed interest in protein-based textiles, though challenges related to yield, cost and industrial-scale spinning have persisted (Clomburg et al., 2017).

Methodology and process development

The investigation employed enzymatic hydrolysis using Viscozyme L, a commercial enzyme mixture from Aspergillus aculeatus, to process yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) biomass into protein pulp suitable for fibre spinning. This treatment eliminates the need for osmotic stabilisers and reducing agents typically required for yeast protoplast preparation, significantly simplifying the bioprocessing workflow (Allen et al., 2025). The protein pulp was subsequently dissolved in N-methyl morpholine N-oxide (NMMO) along with cellulose pulp, creating a dope solution for the lyocell spinning process.

The lyocell technique, recognised as one of the most sustainable methods for producing man-made fibres, employs a closed-loop solvent recovery system that minimises waste and harmful emissions (Fink et al., 2001). The dope preparation involved mixing protein and cellulose powder with NMMO·H₂O at varying concentrations (14–17% solid content) and protein-to-cellulose ratios (1/3 to 1/2). Water removal occurred under vacuum (40–20 mbar) and elevated temperatures (26–95°C) to achieve optimal spinning conditions (Allen et al., 2025).

Dry-jet spinning was executed by extruding the hot dope solution (86–99°C) through circular spinnerets (100 μm diameter) at pressures of 16–22 Pa, followed by a 40 mm air gap before solidification in chilled water (6°C). This configuration facilitated stretching, drawing and relaxation processes that influence fibre crystallinity, orientation and mechanical properties. Both batch and continuous processes were developed, with the continuous process demonstrating stable operation exceeding 100 hours of production time (Allen et al., 2025).

Fibre properties and performance characteristics

The biomanufactured fibres exhibited linear density values ranging from 1.27 to 1.55 dtex, with tenacity measurements between 16 and 23 cN/tex. Notably, the strength values represent a 50% improvement over natural protein fibres such as wool, addressing a historical limitation of regenerated protein materials (Allen et al., 2025). Elongation ranged from 5.4 to 10.8%, with loop tenacity between 3.9 and 5.5 cN/tex, indicating satisfactory durability for textile applications.

Chemical composition analysis confirmed protein content between 25.8 and 38.4% in the finished fibres, consistent with expectations given that input yeast biomass comprises approximately 75% protein and 25% impurities from fermentation. Rheological characterisation revealed zero shear viscosity values ranging from 10,730 to 59,200 Pa·s at 85°C, with the continuous production process maintaining an average of 27,000 Pa·s throughout extended trials (Allen et al., 2025).

The continuous spinning process demonstrated exceptional stability, with consistent quality parameters maintained throughout production runs. Refractive index measurements averaged 1.4900, whilst solid content remained at 14.2%. However, the ion exchange system’s capacity for NMMO recycling was reduced to approximately one-third of standard lyocell process levels, though full capacity was restored following column regeneration (Allen et al., 2025).

Waste yeast biomass as sustainable feedstock

A critical aspect of the research involved comparing food-grade inactive dry yeast with spent yeast from brewery operations, addressing concerns about competition with food supply chains. Laboratory-scale comparisons revealed that waste yeast, after dry-sifting to remove particles larger than 250 μm, produced protein pulp with comparable characteristics to primary yeast material (Allen et al., 2025). While waste yeast yielded lower recovery rates (39% versus 66.7%), the protein and ash contents of resulting products were essentially equivalent.

Rheological testing demonstrated that dope solutions prepared from both biomass sources exhibited similar viscosity parameters, confirming the suitability of waste yeast for industrial applications. Spinning tests conducted under comparable conditions showed completely stable behaviour for both feedstocks, with resulting fibres displaying equivalent physical and mechanical properties (Allen et al., 2025). This discovery holds profound implications for circular economy strategies, as waste yeast biomass can have significantly lower costs and environmental impacts than food-grade alternatives.

Life cycle assessment and environmental performance

The life cycle assessment (LCA) evaluated biomanufactured protein fibres against wool, polyester, cashmere, lyocell and precision fermentation alternatives across multiple environmental metrics. The climate change footprint was estimated at 5.39 kg CO₂ per kilogram of fibre, with manufacturing contributing approximately 73.1% of total emissions. Notably, steam usage within manufacturing accounted for 57.3% of the footprint (Allen et al., 2025). This performance proved competitive with most assessed fibres, surpassing all except polyester.

Energy resources consumption measured 81.2 MJ per kilogram, with manufacturing responsible for 73.5% of nonrenewable energy inputs. Water use registered 0.518 m³ world equivalent deprived per kilogram, substantially lower than all competitors except lyocell. Manufacturing contributed 54.3% of water consumption, with electricity usage representing 34.5% of the total footprint (Allen et al., 2025). These findings demonstrate the environmental advantages of fermentation-based protein fibres over traditional agricultural textiles.

Land use analysis revealed particularly striking results, with biomanufactured fibres requiring only 12.4 points per kilogram compared to wool’s 7,740 points. Manufacturing accounted for 54.4% of land use, with electricity comprising 33.9% of the total footprint. The reduced land footprint directly supports the study’s central thesis: biomanufacturing can liberate agricultural land for food production whilst maintaining textile fibre supplies (Allen et al., 2025; Tilman et al., 2011).

Techno-economic analysis and scalability

The techno-economic model (TEM) examined two integrated processes: biomass conversion to protein pulp and subsequent fibre production through lyocell spinning. The base case scenario, operating at 6,750 tonnes annual production, yielded a levelised cost of $6,080 per tonne ($6.08 per kilogram) of dry fibre. Analysis demonstrated that production costs decrease with increasing capacity, exhibiting classical economies of scale (Allen et al., 2025).

Sensitivity analysis identified two critical parameters influencing economic viability: product fibre rate and downstream protein yield from biomass. Improvements in protein recovery could enable lower levelised costs without additional scaling, suggesting opportunities for process optimisation. The downstream protein yield particularly influences overall economics, with values ranging from 40% to 60% by weight significantly impacting final costs (Allen et al., 2025).

Infrastructure requirements, supply chain logistics and industrial adoption represent potential bottlenecks beyond direct manufacturing considerations. Allen and colleagues addressed these challenges in a companion policy analysis, highlighting systemic issues including limited funding for capital-intensive manufacturing, labour shortages and underdeveloped industrial infrastructure. The authors advocated for enhanced integration of industrial and trade policies, workforce development programmes and novel funding mechanisms for deep-tech manufacturing (Demirel & Adler, 2024).

Broader implications and sustainability considerations

Fermentation-based fibres offer potential to revitalise rural economies by creating novel value chains that transform spent yeast into textiles whilst fostering local employment opportunities. The approach provides an ethical alternative to conventional cotton production, which frequently involves problematic labour practices and worker welfare concerns. However, realising these social benefits requires deliberate attention to workforce development, community engagement and equitable supply chain structures (Allen et al., 2025).

Biodiversity considerations further strengthen the case for biomanufactured textiles. By sourcing proteins sustainably from spent yeast rather than agricultural systems, this approach reduces ecosystem disruption while requiring substantially less land than plant-based fibres. The materials’ biodegradability addresses textile waste concerns, particularly the environmental damage associated with synthetic microfibres, i.e. microplastics (Carney Almroth et al., 2018). Production employs fewer agrochemicals and pesticides than conventional cotton, reducing water and soil contamination risks.

The lyocell closed-loop process minimises solvent waste and environmental release, with NMMO recovery rates exceeding 99% in optimised systems. This contrasts sharply with conventional textile processing, which contributes significantly to water pollution through dyeing and finishing operations (Allen et al., 2025). The integration of waste biomass streams from existing fermentation industries further enhances sustainability credentials whilst potentially approaching zero or negative feedstock costs.

Conclusions and future directions

This comprehensive investigation demonstrates that biomanufacturing protein fibres from yeast biomass represents a technically viable and environmentally advantageous alternative to traditional textile materials. The achievement of continuous spinning for over 100 hours with stable quality parameters, combined with mechanical properties exceeding natural protein fibres by 50%, addresses historical limitations that curtailed earlier regenerated protein products (Allen et al., 2025). The successful utilisation of waste yeast biomass critically advances circular economy objectives whilst eliminating competition with food supply chains.

Life cycle assessment results confirm substantial environmental benefits, particularly regarding land and water use – the metrics most directly linked to food security concerns. The capacity to produce textiles without occupying arable land supports United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 2: Zero Hunger, while simultaneously addressing the textile industry’s ecological footprint. Techno-economic analysis indicates commercial viability at scale, with production costs of approximately $6 per kilogram at 6,750 tonnes annual capacity (Allen et al., 2025).

Future research priorities should emphasise optimising protein yields from biomass, developing additional waste feedstock sources and refining spinning parameters to enhance mechanical properties further. Integration with existing fermentation industries offers immediate opportunities for implementation, leveraging established infrastructure and spent yeast streams from brewing, biofuel and pharmaceutical production. Policy frameworks supporting deep-tech manufacturing, workforce development and industrial infrastructure will prove essential for scaling this technology beyond pilot demonstration (Demirel & Adler, 2024).

The successful deployment of fermentation-based protein fibres could significantly advance sustainable development goals, ensuring textile production complements rather than compromises global food security.

#Wasteless, #recycle

Dario Dongo

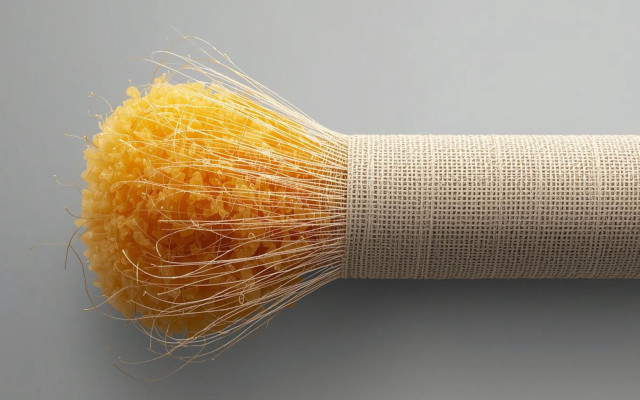

Cover art copyright © 2025 Dario Dongo (AI-assisted creation)

References

- Allen, B. D., Ghotra, B., Kosan, B., Köhler, P., Krieg, M., Kindler, C., Sturm, M., & Demirel, M. C. (2025). Impact of biomanufacturing protein fibers on achieving sustainable development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(45), Article e2508931122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2508931122

- Brooks, M. (2009). Regenerated protein fibres: A preliminary review. In Handbook of Textile Fibre Structure (pp. 234–265). Woodhead Publishing.

- Carney Almroth, B. M., Åström, L., Roslund, S., Petersson, H., Johansson, M., & Persson, N.-K. (2018). Quantifying shedding of synthetic fibers from textiles: A source of microplastics released into the environment. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 25(2), 1191–1199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-0528-7

- Clomburg, J. M., Crumbley, A. M., & Gonzalez, R. (2017). Industrial biomanufacturing: The future of chemical production. Science, 355(6320), Article aag0804. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aag0804

- Demirel, M., & Adler, D. (2024). Threading the innovation chain: Scaling and manufacturing deep tech in the United States. American Affairs, 8(3), 58–79. https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2024/11/threading-the-innovation-chain-scaling-and-manufacturing-deep-tech-in-the-united-states/

- Fink, H.-P., Weigel, P., Purz, H., & Ganster, J. (2001). Structure formation of regenerated cellulose materials from NMMO-solutions. Progress in Polymer Science, 26(9), 1473–1524. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6700(01)00025-9

- The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024 (SOFI report) – Financing to end hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms. FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. Rome, 2024. ISBN 978-92-5-138882-2. https://doi.org/10.4060/cd1254en

- Tilman, D., Balzer, C., Hill, J., & Befort, B. L. (2011). Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(50), 20260–20264. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1116437108

Dario Dongo, lawyer and journalist, PhD in international food law, founder of WIISE (FARE - GIFT - Food Times) and Égalité.