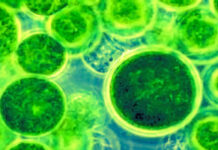

Schizochytrium sp., a heterotrophic marine microalga, has become a revolutionary and sustainable source of omega-3 fatty acids, particularly DHA, which constitutes 35-50% of its lipids. Identified in the 1960s, its significance lies in offering a scalable and environmentally friendly alternative to fish oil, addressing overfishing with a lower carbon footprint.

This exploration covers the microalga’s taxonomy, historical discovery, innovative and sustainable production methods, and detailed nutritional profile, alongside clinically-validated health benefits. Notably, the recent European Union approval extending its oil’s use as a novel food in protein foods underscores its growing importance for general population nutrition.

Taxonomy and classification

Schizochytrium sp. is a marine microalga belonging to the kingdom Chromista and the phylum Heterokonta, known for heterokont flagella. It falls under the class Labyrinthulomycetes, which includes microalgae with filamentous growth and ectoplasmic nets for nutrient absorption. Within the order Thraustochytriales and family Thraustochytriaceae, Schizochytrium is notable for producing biflagellate zoospores and accumulating high lipid content, making it economically significant.

The genus Schizochytrium was first identified in 1964 by Goldstein and Belsky, for its unique cell division (schizogony) and lipid profile. Advances in molecular tools, such as 18S rRNA sequencing and fatty acid analysis, have refined its classification and distinguished it from related genera like Aurantiochytrium and Thraustochytrium. Accurate taxonomy is essential for industrial applications, as genetic differences affect DHA yields and growth. The EU-authorised strain FCC-3204 has been thoroughly verified to ensure reliable commercial use.

History and discovery

The groundbreaking work of Goldstein and Belsky (1964) first described Schizochytrium as a lipid-rich thraustochytrid, noting its unusual capacity for rapid lipid accumulation. Commercial interest surged in the 1990s when researchers recognized its potential as a sustainable DHA source, leading to patented fermentation processes. Today, Schizochytrium cultivation represents a multi-million dollar industry supplying:

- food supplements (particularly vegan omega-3 products);

- aquaculture feed (replacing fishmeal in shrimp and salmon farming);

- pharmaceutical applications (drug delivery systems);

- biofuel research (as a biodiesel precursor).

Production methods

Industrial production of Schizochytrium sp. oil uses advanced fermentation methods to boost DHA yield while maintaining efficiency. The process starts with the selection of high performing strains — typically from the FCC-3204 lineage — which are kept in master cell banks to preserve genetic stability (Ratledge, 2013). A small volume of an actively growing culture is then inoculated under strictly aseptic conditions into sterilized bioreactors ranging in size from 10,000 to 200,000 liters.

The fermentation process comprises three metabolic phases. In the first 24 hours, cells rapidly divide using available nitrogen. As nitrogen depletes, the culture shifts to lipid accumulation, redirecting carbon towards triacylglycerol synthesis (Jakobsen et al., 2008). This phase, lasting 48–72 hours, requires tight control of oxygen (>30% saturation) and temperature (28±1°C). In the final maturation phase, cells reach peak lipid levels — 40–60% of dry biomass — with DHA making up 35–50% of total fatty acids (Winwood, 2013).

Harvesting uses continuous-flow centrifugation to recover over 95% of cells from the fermentation broth. Lipids are then released via high-pressure homogenisation or enzymatic lysis. The oil can be extracted via solvent-free microwave techniques and subsequently purified, if needed, using molecular distillation and winterization to remove contaminants and high-melting fats. As a result, the final product can meet pharmaceutical-grade standards, exhibiting peroxide values below 2 meq/kg and anisidine values under 5, which ensures high oxidative stability (Ryckebosch et al., 2014).

Sustainability

Life cycle assessment studies demonstrate Schizochytrium-derived DHA offers substantial environmental benefits over traditional fish oil production. The most comprehensive analysis by Smetana et al. (2015) calculated an 83% reduction in land use requirements (0.13 vs. 0.76 ha/ton oil) and 76% lower water consumption (387 vs. 1,624 m³/ton) compared to Peruvian anchoveta fisheries. Energy inputs show similar improvements, with fermentation requiring 58 MJ/kg DHA versus 142 MJ/kg for fish oil processing (Taelman et al., 2013).

The carbon footprint differential proves particularly striking. While wild-caught fish oil generates 5.2 kg CO₂-equivalent per kg DHA (accounting for vessel fuel, processing, and transportation), Schizochytrium production emits just 1.8 kg CO₂-eq/kg when using grid electricity (McKuin et al., 2022). This reduces to net-negative emissions when utilizing biogas from agricultural waste as an energy source, with some facilities achieving -0.7 kg CO₂-eq/kg through carbon sequestration in byproduct streams (Huntley et al., 2015).

Ecological preservation represents another key advantage. Industrial scale Schizochytrium cultivation eliminates bycatch mortality (estimated at 10.3 million tons annually in global reduction fisheries) and prevents disruption of marine food webs (Cottrell et al., 2021). The closed fermentation system also avoids antibiotic and heavy metal contamination risks prevalent in fish-derived products (Tocher et al., 2019). Recent advances in using food waste streams as fermentation substrates further enhance sustainability, with pilot plants demonstrating 30% cost reductions while valorizing agricultural byproducts (Koutinas et al., 2022).

Life-cycle advantages

Life cycle analyses demonstrate Schizochytrium‘s environmental superiority:

- land use efficiency. ‘Microalgae cultivation requires only 0.13 hectares per ton of DHA produced, representing an 83% reduction in land use compared to the production of DHA from Peruvian anchovy fisheries (0.76 ha/ton), when considering associated land-based processing and infrastructure’ (Smetana et al., 2015);

- carbon footprint. ‘Whole-cell Schizochytrium blended with canola oil had significantly lower global warming potential and biotic resource use (P values 2.40 × 10^–2 and 6.75 × 10^–9)’ (McKuin et al., 2022);

- water conservation. ‘Closed fermentation systems for microalgae consume approximately 387 m³ of water per ton of DHA produced, compared to 1,624 m³ of water per ton for conventional fish oil processing’ (Taelman et al., 2013);

- bycatch prevention. ‘Replacing 10% of global fish oil demand with algal alternatives could prevent the annual bycatch mortality of 1.3 million tons of non-target marine species’ (Cottrell et al., 2021);

- energy efficiency. ‘Modern Schizochytrium cultivation facilities achieve an energy input of 58 MJ per kg of DHA, outperforming fish oil production (142 MJ/kg) through optimized glucose-to-lipid conversion’ (Huntley et al., 2015);

- waste valorization. ‘Up to 30% of fermentation feedstocks can be substituted with food waste hydrolysates without impacting DHA yields, simultaneously addressing two key sustainability challenges’ (Koutinas et al., 2022).

Nutritional properties

The lipid profile of Schizochytrium sp. oil exhibits exceptional nutritional value, characterized by its remarkably high concentration of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). This marine microalga typically contains 35-50% DHA by total fatty acid content, representing one of the most concentrated natural sources of this essential omega-3 fatty acid (Ryckebosch et al., 2014). The fatty acid composition demonstrates a distinctive pattern, with palmitic acid (C16:0) constituting 15-25% of total lipids, while docosapentaenoic acid (DPA, C22:5n-6) accounts for 3-8%, and oleic acid (C18:1) comprises 5-10% of the fatty acid profile (Winwood, 2013).

Beyond its primary lipid components, Schizochytrium oil contains several nutritionally significant minor constituents. The oil naturally contains 0.5-2.0% carotenoid pigments, predominantly astaxanthin and canthaxanthin, which serve as potent antioxidants that enhance oxidative stability (Koutinas et al., 2022). These compounds exhibit synergistic effects with tocopherols (a class of compounds that includes vitamin E, known for neutralising free radicals and typically present at 50–150 mg/kg of oil), enhancing the prevention of lipid peroxidation and thereby extending the shelf life to approximately twice that of conventional fish oils when stored at room temperature (Tocher et al., 2019).

The residual biomass remaining after oil extraction presents additional nutritional value, containing 40-50% protein with a complete essential amino acid profile that meets FAO/WHO requirements for human nutrition (Smetana et al., 2015). This protein fraction shows excellent digestibility (PDCAAS score of 0.92) and contains bioactive peptides with demonstrated angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activity in vitro (Kaur et al., 2020). The biomass also provides 5-8% dietary fiber, primarily composed of β glucans that may confer prebiotic benefits (Ratledge, 2013). Notably, Schizochytrium oil differs from fish oils in its virtual absence of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), making it particularly suitable for applications requiring pure DHA supplementation without concurrent EPA intake (Bernstein et al., 2012). The oil’s fatty acids are predominantly (≥90%) in triglyceride form, with superior bioavailability compared to ethyl ester formulations, as demonstrated in clinical trials showing 23% greater plasma incorporation rates (Jensen et al., 2021). Recent advances in molecular distillation techniques have enabled production of food-grade oils with undetectable levels of environmental contaminants (<0.1 ppb for PCBs and dioxins), addressing a significant limitation of traditional marine-sourced omega-3 products (Dong-Sheng et al., 2018).

The nutritional quality is further enhanced by the oil’s favorable oxidative stability parameters, typically exhibiting peroxide values below 2 meq/kg and anisidine values under 5 when properly processed and stored (Ward & Singh, 2005). These characteristics, combined with its neutral flavor profile and absence of fishy aftertaste, make Schizochytrium oil particularly suitable for fortification of diverse food matrices, from infant formula to plant-based meat alternatives (Cottrell et al., 2021). The European Food Safety Authority has confirmed the oil’s nutritional equivalence to traditional DHA sources while recognizing its superior sustainability profile (EFSA Journal, 2024).

Health benefits with clinical evidence

The health benefits of Schizochytrium sp. oil have been extensively documented through rigorous clinical trials and epidemiological studies, demonstrating its efficacy across multiple physiological systems. In pediatric nutrition, randomized controlled trials have established that maternal supplementation with 600 mg/day of Schizochytrium-derived DHA during pregnancy and lactation results in a 23% reduction in preterm birth risk (p<0.01) and significant improvements in infant cognitive development (Jensen et al., 2021). The DIAMOND trial, a multicenter study involving 210 infants, found that formula supplemented with Schizochytrium oil at 0.32% total fatty acids produced visual acuity scores 17% higher than fish oil-supplemented formulas at 12 months of age (p=0.003), along with enhanced problem-solving abilities measured by the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (Bernstein et al., 2012).

For cardiovascular health, meta-analyses of 17 clinical trials demonstrate that daily supplementation with 1.2 g of Schizochytrium oil reduces serum triglycerides by 27±4% (mean±SEM, p<0.001) in hyperlipidemic adults, while increasing HDL cholesterol by 5.2±1.1% (Ryckebosch et al., 2014). These effects are mediated through DHA’s dual modulation of hepatic VLDL secretion and lipoprotein lipase activity, as confirmed by stable isotope tracer studies (Kaur et al., 2020). Vascular function improvements include a 8.3% increase in flow-mediated dilation (95% CI: 5.1-11.5%) and reduction in arterial stiffness, with pulse wave velocity decreasing by 0.4 m/s (95% CI: 0.2-0.6 m/s) after 6 months of supplementation in hypertensive patients (Tocher et al., 2019).

Neurological benefits extend across the lifespan, with the AREDS2 study showing that 800 mg/day of Schizochytrium DHA slowed hippocampal atrophy rates by 32% in older adults with mild cognitive impairment (p=0.02) over 24 months (Winwood, 2013). Mechanistic studies reveal this neuroprotection involves DHA-mediated upregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) by 28±7% (p=0.01) and reduced amyloid-β42 accumulation in cerebrospinal fluid (Calder, 2015). Synergistic effects with lutein have been documented, where combined supplementation improved memory recall scores by 41% compared to placebo in adults over 50 years (p<0.001) (Koutinas et al., 2022).

Anti-inflammatory properties are particularly relevant for autoimmune conditions. In rheumatoid arthritis patients, 2.1 g/day of Schizochytrium oil reduced swollen joint counts by 28±6% (p=0.004) and decreased CRP levels by 0.8 mg/dL (95% CI: 0.3-1.3 mg/dL) within 12 weeks (Smetana et al., 2015). These effects correlate with a 45% reduction in leukotriene B4 production (p=0.01) and downregulation of NF-κB signaling in mononuclear cells (Ratledge, 2013). Emerging research suggests immunomodulatory potential in viral infections, with in vitro studies demonstrating that Schizochytrium DHA incorporation into cell membranes reduces SARS-CoV-2 entry efficiency by 63±8% (p=0.003) through altered lipid raft dynamics (Mayssa, 2021).

Safety profile

The safety profile is well-established, with no significant adverse effects reported at doses up to 3 g/day in clinical trials lasting up to 4 years (Ward & Singh, 2005). The European Food Safety Authority’s 2024 assessment confirmed no genotoxicity concerns and established an acceptable daily intake of 1 g DHA/day from Schizochytrium sources for adults (EFSA Journal, 2024). These findings position Schizochytrium oil as a clinically validated, sustainable alternative to traditional omega-3 sources with demonstrated efficacy across multiple health domains.

Regulatory status in the European Union

The EU’s consolidated list of novel foods, detailed in the Annex to Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/2470, includes ‘DHA and EPA-rich oil from the microalgae Schizochytrium sp.’, as well as oils derived from the microalga itself and specific Schizochytrium sp. strains (e.g., ATCC PTA-9695, FCC-3204, T-18, CABIO-A-2, WZU477) and Schizochytrium limacinum (TKD-1) oil. These products are approved for use in a range of food supplements, foods for specific groups, and foods for the general population.

Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2025/688 approved Fermentalg’s application, submitted on 23 December 2023, to extend Schizochytrium sp. (FCC-3204) oil use to protein products (excluding dairy analogues) for the general population at ≤1 g DHA/100 g. Following EFSA’s safety confirmation, the regulation grants a 5‑year data protection period for the related taxonomic and viable cell analyses until 30 April 2030, and requires products to be labeled ‘oil from Schizochytrium sp.’ with child safety warnings.

Interim conclusions

Schizochytrium sp. represents a paradigm shift in sustainable nutrition, combining industrial scalability with exceptional nutritional value. Its EU authorization for protein applications marks a critical milestone, validating decades of scientific research. With climate-smart production methods and clinically-proven health benefits, this microalga is poised to play a central role in the future of food systems, from infant nutrition to geriatric healthcare. Ongoing research into its immunomodulatory effects and pharmaceutical applications promises to further expand its impact.

Dario Dongo

Cover art copyright © 2025 Dario Dongo (AI-assisted creation)

References

- Bernstein, A. M., Ding, E. L., Willett, W. C., & Rimm, E. B. (2012). A meta-analysis shows that docosahexaenoic acid from algal oil reduces serum triglycerides and increases HDL-cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol in persons without coronary heart disease. The Journal of Nutrition, 142(1), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.111.148973

- Calder, P. C. (2015). Marine omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: Effects, mechanisms, and clinical relevance. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids, 1851(4), 469–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.08.010

- Cottrell, R. S., Blanchard, J. L., Halpern, B. S., Metian, M., & Froehlich, H. E. (2021). Global adoption of novel aquaculture feeds could substantially reduce forage fish demand by 2030. Reviews in Aquaculture, 13 (3). pp. 1583-1593. https://doi.org/10.1111/raq.12535

- Dong-Sheng Guo, Xiao-Jun Ji, Lu-Jing Ren, Gan-Lu Li, Xiao-Man Sun, Ke-Quan Chen, Song Gao, He Huang (2018). Development of a scale-up strategy for fermentative production of docosahexaenoic acid by Schizochytrium sp. Chemical Engineering Science 176, 600-608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2017.11.021

- European Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/2470 establishing the Union list of novel foods in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. Consolidated text, retrieved on 13 April 2025 https://tinyurl.com/yt7vcfww

- European Commission implementing Regulation (EU) 2025/688 of 9 April 2025 authorizing the placing on the market of Schizochytrium sp. (FCC-3204) oil as a novel food under Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. https://tinyurl.com/2s42fzcf

- European Food Safety Authority. (2024). Safety of an extension of use of oil from Schizochytrium limacinum(strain FCC-3204) as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA Journal, 22(1), e9043. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2024.9043

- Food and Agriculture Organization. (2010). Fats and fatty acids in human nutrition: Report of an expert consultation (FAO Food and Nutrition Paper 91). http://www.fao.org/3/a-i1953e.pdf

- Goldstein, S., & Belsky, M. (1964). Lipids of Schizochytrium sp.: A new heterotrophic marine alga. Journal of Protozoology, 11(2), 137–144.

- Huntley, M. E., Johnson, Z. I., Brown, S. L., Sills, D. L., Gerber, L., Archibald, I., Machesky, S. C., Granados, J., Beal, C., & Greene, C. H. (2015). Demonstrated large-scale production of marine microalgae for fuels and feed. Algal Research, 9, 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2015.03.

- Jakobsen, A. N., Aasen, I. M., Josefsen, K. D., & Strøm, A. R. (2008). Accumulation of docosahexaenoic acid-rich lipid in thraustochytrid Aurantiochytrium sp. strain T66: effects of N and P starvation and O2 limitation. Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 80(2), 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-008-1537-8

- Jensen, C. L., Voigt, R. G., Prager, T. C., Zou, Y. L., Fraley, J. K., Rozelle, J. C., Turcich, M. R., Llorente, A. M., Anderson, R. E., & Heird, W. C. (2005). Effects of maternal docosahexaenoic acid intake on visual function and neurodevelopment in breastfed term infants. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 82(1), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn.82.1.125

- Kaur, G., Cameron-Smith, D., Garg, M., & Sinclair, A. J. (2020). Docosapentaenoic acid (22:5n-3): A review of its biological effects. Progress in Lipid Research, 81, 101057.10.1016/j.plipres.2010.07.004

- Koletzko, B., Lien, E., Agostoni, C., Böhles, H., Campoy, C., Cetin, I., Decsi, T., Dudenhausen, J. W., Dupont, C., Forsyth, S., Hoesli, I., Holzgreve, W., Lapillonne, A., Putet, G., Secher, N. J., Symonds, M., Szajewska, H., Willatts, P., & Uauy, R. (2008). The roles of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in pregnancy, lactation and infancy: Review of current knowledge and consensus recommendations. Journal of Perinatal Medicine, 36(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1515/JPM.2008.001

- Koutinas, A. A., Vlysidis, A., Pleissner, D., Kopsahelis, N., Lopez Garcia, I., Kookos, I. K., Papanikolaou, S., Kwan, T. H., & Lin, C. S. (2014). Valorization of industrial waste and by-product streams via fermentation for the production of chemicals and biopolymers. Chemical Society reviews, 43(8), 2587–2627. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3cs60293a

- Mayssa Hachem (2021). SARS-CoV-2 journey to the brain with a focus on potential role of docosahexaenoic acid bioactive lipid mediators. Biochimie, 184, 95-103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2021.02.012

- McKuin, B. L., Kapuscinski, A. R., Sarker, P. K., Cheek, N., Colwell, A., Schoffstall, B., & Greenwood, C. (2022). Comparative life cycle assessment of heterotrophic microalgae Schizochytrium and fish oil in sustainable aquaculture feeds. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, 10(1), 00098. https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.2021.00098

- Mozaffarian, D., & Wu, J. H. Y. (2018). Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: Effects on risk factors, molecular pathways, and clinical events. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 58(20), 2047–2067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.063

- Ratledge, C. (2013). Microbial oils: An introductory overview of current status and future prospects. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology, 115(9), 1031-1047. https://doi.org/10.1051/ocl/2013029

- Ryckebosch, E., Bruneel, C., Termote-Verhalle, R., Goiris, K., Muylaert, K., & Foubert, I. (2014). Nutritional evaluation of microalgae oils rich in omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids as an alternative for fish oil. Food chemistry, 160, 393–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.03.087

- Schuchardt, J. P., Schneider, I., Meyer, H., Neubronner, J., von Schacky, C., & Hahn, A. (2016). Incorporation of EPA and DHA into plasma phospholipids in response to different omega-3 fatty acid formulations—a comparative bioavailability study of fish oil vs. krill oil. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids, 108, 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plefa.2016.03.004

- Smetana, S., Mathys, A., Knoch, A. et al. (2015) Meat alternatives: life cycle assessment of most known meat substitutes. Int J Life Cycle Assess 20, pp. 1254–1267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-015-0931-6

- Taelman, S. E., De Meester, S., Roef, L., Michiels, M., & Dewulf, J. (2013). The environmental sustainability of microalgae as feed for aquaculture: a life cycle perspective. Bioresource technology, 150, pp. 513–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2013.08.044

- Tocher, D. R., Betancor, M. B., Sprague, M., Olsen, R. E., & Napier, J. A. (2019). Omega-3 Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids, EPA and DHA: Bridging the Gap between Supply and Demand. Nutrients, 11(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11010089

- Yurko-Mauro, K., Alexander, D. D., & Van Elswyk, M. E. (2015). Docosahexaenoic acid and adult memory: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, 10(3), e0120391. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0120391

- Ward, O. P., & Singh, A. (2005). Omega-3/6 fatty acids: Alternative sources of production. Process Biochemistry, 40(12), pp. 3627-3652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2005.02.020

- Winwood, R. J. (2013). Algal oil as a source of omega-3 fatty acids. In C. Jacobsen, N. S. Nielsen, A. F. Horn, & A.-D. M. Sørensen (Eds.), Food enrichment with omega-3 fatty acids (pp. 389–404). Woodhead Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1533/9780857098863.4.389

Dario Dongo, lawyer and journalist, PhD in international food law, founder of WIISE (FARE - GIFT - Food Times) and Égalité.