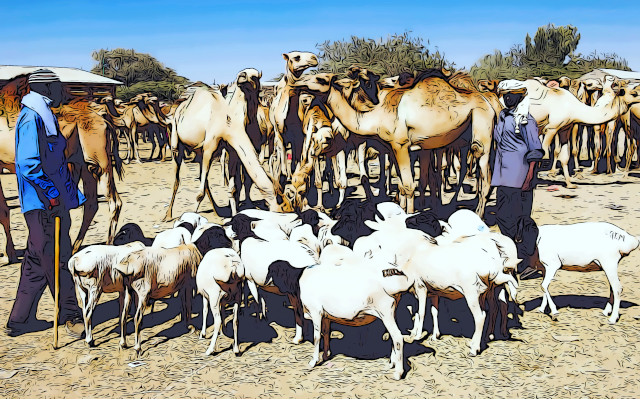

Reducing cattle herds and increasing camels and goats for milk production is a useful option for improving the climate resilience of populations living in the arid and semi-arid areas of northern sub-Saharan Africa. The trend is the subject of a study published in Nature Food.

Milk from camels and goats

Dairy production in northern sub-Saharan Africa plays a major role in ensuring the livelihoods and food security of the local populations-a population of 256 million mostly dependent on agricultural and livestock activities-and neighboring countries.

From this area comes 86% of the milk consumed in all of sub-Saharan Africa, or 30 Mt, broken down into 65% milk from cattle, 25% from goats and 10% from camels. Camel milk, in fact, is still uncommon in Europe, but it is known to have less saturated fat and lactose and more minerals and vitamins (especially vitamin C and B vitamins) than cow’s milk. And in Africa it is rapidly gaining new consumers.

The burden of climate change

Demand for milk in sub-Saharan Africa has increased by 4 percent annually in recent decades and is estimated to triple by 2050. But climate change, with worsening drought, is putting a strain on its production.

Some pastoralist communities in the arid areas (e.g., Wodaâbe in Niger, Massaï in Kenya, Borana in Ethiopia, Nuer in South Sudan, and Fulani in West Africa) have already begun to counteract adversity by increasing goat and camel herds. Compared to cattle, in fact, these animals enjoy greater climate resilience in terms of their resistance to drought and feed shortages. And they produce milk (and meat) in all seasons. Without underestimating the usefulness of diversifying the source of income to better withstand economic, political and ecological instabilities.

The race to diversify herds

The choice to diversify dairy animals is shared by ‘More than 71.5 percent of households surveyed by a Borana community survey of Isiolo County, northern Kenya‘, report the study authors, who aim to identify the areas most affected by this ‘adaptive’ transformation and measure its impact in terms of milk production and environmental sustainability.

‘We found ten cases in the arid areas of NSSA (Northern Sub-Saharan Africa, ed.) where the shift from cattle to goats and camels is already evident (East Pokot and Isiolo County in Kenya; Ngorongoro in Tanzania; Afar, Yabelo, Moyale, and Jijiga in Ethiopia; Somaliland in Somalia; Misseriyya Pastoralists in Sudan; Kaduna and Kano States in Nigeria) and these overlap with the areas we identified as deteriorating (climatically, ed.)‘, indicate the authors of the study.

The ideal model

Finally, by evaluating each variable, the researchers defined the ideal model, that is, the best combination of the herd in terms of

- Maximum milk production,

- Lower water/feed consumption,

- Low greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

As a result, the ideal herd composition in drylands requires a major change

- 9.7 percent cattle, compared with the current 34.7 percent,

- 68.3% goats, compared with 52% at present,

- 22% camels, now at 13.3%.

In semi-arid areas, the ideal combination is instead indicated in

- 24 percent cattle (from the current 47.7 percent),

- 58.3 percent goats (now at 46.3),

- 17.7% camels (now 6%).

The unsurpassed middle ground

The researchers also developed three extreme hypotheses of herd modification:

- 100% goats,

- 100% camels,

- 50% goats and 50% camels.

All extreme solutions Were found to be inconvenient. ‘For example, in the case of the 100% goat scenario, although replacing 100% of cattle with goats has benefits in terms of feed consumption (-15%), water consumption (-33%), and greenhouse gas emission (-9%), milk production in this scenario would decrease by 26%‘, the researchers explain.

Goat and camel milk, demand on the rise

From necessity to virtue. In some sub-Saharan regions, goat and camel milk is in growing demand, fueled in part by the spread of information about their valuable nutritional profile.

‘In Samburu County., in Kenya, where historically camel farming was not common, it has been reported that families currently prefer camel milk to other types of milk. Over the past decade, the market for goat and camel products has also expanded significantly in NSSA (North Sub-Saharan Africa, ed.) with increasing demand and growing awareness of the health benefits of these products (particularly in the case of camel milk/meat). For example, rapid growth in demand for camel milk and the camel milk value chain has been reported in Somalia‘.

The obstacles

Although demand is growing, some difficulties remain in reshaping pastoralism. Two out of all:

- economic obstacles, with female camels costing three times as much as cows. ‘In Kenya’s livestock markets in 2021, a camel cost US$421-526, which was equivalent to 2-3 cattle or 10 goats.’

- ”the lack of knowledge and skills related to animal husbandry and management practices and the initial costs of purchasing additional equipment and technology needed to run goats and camels. ‘When switching from cattle to camels, although a mature camel may offer a higher rate of economic return than cattle and goats (depending on the type of herd, breed of livestock, feeding situation, location, etc.), camels may have financial disadvantages due to their lower reproductive rate than other species, due to their relatively late puberty (3 years old) and longer calving interval (2 years)‘.

The wishes of researchers

The aforementioned benefits and difficulties require first and foremost a political commitment to support pastors engaged in this transition.

Stakeholders and research organizations in animal husbandry ‘should adopt a multi-sectoral approach that prioritizes future research on breeding services, disease control, and nutrition for these species.’

Such an effort, ‘should emphasize both heat-resistant cattle breeds and increased goat/camel milk production. Finally, improvements in goat and camel dairy supply chains, such as processing technologies to improve markets for goat and camel dairy products, facilities to transport milk to local markets, and distribution and processing infrastructure for production markets, are essential to harness the full potential of changes in herd composition and realize the vision of sustainable and food-secure dairy production in the NSSA (North Sub-Saharan Africa, ed.) by 2030‘, conclude the study authors.

Notes

(1) Rahimi, J., Fillol, E., Mutua, J.Y. et al. A shift from cattle to camel and goat farming can sustain milk production with lower inputs and emissions in north sub-Saharan Africa’s drylands. Nat Food 3, 523-531 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-022-00543-6

Professional journalist since January 1995, he has worked for newspapers (Il Messaggero, Paese Sera, La Stampa) and periodicals (NumeroUno, Il Salvagente). She is the author of journalistic surveys on food, she has published the book "Reading labels to know what we eat".