Iron-deficiency anaemia represents a critical global health challenge, affecting approximately one billion people worldwide (Gao et al., 2025). While conventional dietary interventions rely heavily on animal-based foods or plant sources with limited bioavailability, emerging research suggests that microalgae may offer a sustainable and highly bioaccessible alternative. A comprehensive study by Gao and colleagues (2025) at ETH Zurich has systematically evaluated the iron bioaccessibility and bioaccumulation capacity of three commercially relevant microalgal species under varying production conditions, providing crucial insights for developing novel iron-rich food ingredients.

The research team investigated three microalgae species: Arthrospira platensis (Spirulina), Galdieria sulphuraria, and Chlorella vulgaris, cultivating them under autotrophic, heterotrophic, and mixotrophic conditions using both standard and iron-enriched media (Gao et al., 2025). The study employed the standardised INFOGEST 2.0 protocol to simulate gastrointestinal digestion, a methodology widely recognised for assessing nutrient bioaccessibility (Brodkorb et al., 2019). Iron content analysis was performed using inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) following microwave-assisted acid digestion, ensuring precise quantification of both total and bioaccessible iron fractions.

A critical methodological consideration involved implementing rigorous washing protocols to distinguish between surface-bound (biosorbed) and intracellular (bioaccumulated) iron. Different washing solutions – EDTA, Na₂EDTA, and ultrapure water – were compared, with species-specific optimisation revealing that C. vulgaris required Na₂EDTA treatment to effectively remove extracellular iron, whilst Milli-Q water proved sufficient for A. platensis and G. sulphuraria (Gao et al., 2025). This distinction proves essential, as biosorbed iron demonstrates considerably lower bioaccessibility and may potentially contribute to gastrointestinal inflammation through stimulation of pathogenic bacteria (Paganini & Zimmermann, 2017).

Iron bioaccumulation across cultivation modes

The investigation revealed substantial variations in iron content depending on cultivation mode and species. Under standard medium conditions, autotrophic cultivation generally promoted higher iron bioaccumulation, with A. platensis achieving 563.4 mg/kg and C. vulgaris reaching 326.5 mg/kg (Gao et al., 2025). Notably, G. sulphuraria deviated from this pattern, demonstrating peak iron accumulation (238.9 mg/kg) under mixotrophic conditions. This species-specific response may relate to differential iron uptake pathways and the presence of iron-chelating compounds such as phycocyanin, which has been documented to possess iron-binding capacity (Bermejo et al., 2008; Isani et al., 2022a).

The biomass productivity analysis revealed that heterotrophic and mixotrophic cultivation modes significantly enhanced growth rates compared to autotrophic conditions. For G. sulphuraria, mixotrophic cultivation yielded biomass productivity of 3.6 g/L/day, representing a fourfold increase over autotrophic cultivation (Gao et al., 2025). However, this increased productivity came at the expense of reduced iron content in C. vulgaris, which decreased from 326.5 mg/kg under autotrophic conditions to 72.9 mg/kg under mixotrophic mode. These findings underscore the necessity of balancing biomass yield with nutritional quality when optimising microalgal production for iron supplementation applications.

Iron bioaccessibility: the critical nutritional parameter

While total iron content provides valuable information, iron bioaccessibility – the fraction released from the food matrix during digestion and available for absorption – represents the more functionally relevant parameter for addressing nutritional deficiencies. The study demonstrated that heterotrophic cultivation consistently enhanced iron bioaccessibility across species, with C. vulgaris achieving 76.3% and G. sulphuraria reaching 66.9% under these conditions (Gao et al., 2025). In contrast, autotrophically cultivated biomass exhibited markedly lower bioaccessibility: 18.4% for A. platensis, 39.8% for G. sulphuraria, and 41.8% for C. vulgaris.

These differences likely stem from variations in cell wall ultrastructure and composition across cultivation modes. Previous research has established that cell wall thickness in C. vulgaris increases from 82 to 114 nm as cultures transition from exponential to stationary phase, comprising two distinct layers that impede nutrient release (Canelli et al., 2021). Similarly, protein bioaccessibility studies have revealed cultivation-dependent variations in digestibility, with strain-specific responses further complicating predictive frameworks (Canelli et al., 2023). The inverse relationship between iron content and bioaccessibility observed in autotrophically cultivated G. sulphuraria suggests that high intracellular iron concentrations may alter storage mechanisms in ways that reduce digestive accessibility, warranting further investigation at the molecular level.

Iron enrichment strategies and biofortification potential

A particularly promising avenue explored in this research involved manipulating medium iron concentration to enhance bioaccumulation. G. sulphuraria demonstrated exceptional tolerance to elevated iron levels, maintaining robust growth even at 150-fold standard iron concentrations, whilst achieving a 7.6-fold increase in biomass iron content to 1,472.4 mg/kg (Gao et al., 2025). This remarkable biofortification capacity likely relates to the species’ acidophilic nature, as growth at pH <2 substantially increases iron solubility and cellular uptake (Abinandan et al., 2019). However, this enhanced bioaccumulation was accompanied by a relative decline in bioaccessibility from 36.8% to 17.1%, illustrating the complex trade-offs inherent in nutritional optimisation strategies.

A. platensis exhibited more limited tolerance to iron enrichment, with negative growth effects observed beyond fivefold standard concentrations, yielding only modest increases in iron content (Gao et al., 2025). Previous research has documented considerably higher bioaccumulation potential in A. platensis using alternative iron sources such as iron(III) citrate or chelated FeEDTA compounds, which enhance uptake efficiency compared to ferrous sulphate (Kougia et al., 2023). The form of iron and the presence of adequate EDTA for chelation represent critical variables requiring meticulous optimisation, as excessive EDTA can exert toxicity whilst insufficient levels lead to iron precipitation. Future research should systematically evaluate iron speciation effects across multiple strains to establish robust biofortification protocols for industrial applications.

Absolute bioaccessible iron: a holistic nutritional metric

The concept of absolute bioaccessible iron, calculated by multiplying total iron content by fractional bioaccessibility, provides a more comprehensive assessment of nutritional value than either parameter considered independently. This metric revealed that G. sulphuraria cultivated autotrophically with 150-fold iron enrichment delivered 251.6 mg/kg of bioaccessible iron, representing the highest value observed across all conditions tested (Gao et al., 2025). This figure substantially exceeds values obtained from conventional foods, including the burger patty (21.3 mg/kg fresh weight), smoked salmon (2.3 mg/kg fresh weight), and fried tofu (4.4 mg/kg fresh weight) analysed in the comparative assessment.

While animal-based foods demonstrated high iron bioaccessibility (73.4% for burger patty, 89.8% for salmon), their lower absolute iron content resulted in considerably reduced bioaccessible iron yields. Plant-based tofu exhibited both low iron content and poor bioaccessibility (19.3%), likely attributable to high concentrations of absorption inhibitors including phytic acid, polyphenols, and tannins (Yin et al., 2020). In practical terms, consuming 45 g of burger patty would provide approximately 1.0 mg of bioaccessible iron, equivalent to merely 3.8 g of iron-enriched G. sulphuraria powder. These comparisons highlight microalgae as concentrated, highly efficient iron sources requiring minimal serving sizes to achieve meaningful nutritional impact.

Implications for sustainable nutrition and food security

The findings present compelling evidence for microalgae as promising candidates for addressing iron-deficiency anaemia through dietary intervention. Beyond their high bioaccessible iron content, microalgae offer additional advantages including natural enrichment in ascorbic acid (approximately 2,000 mg/kg in A. platensis), a potent iron absorption enhancer, and minimal concentrations of absorption inhibitors such as phytate compared to conventional plant sources (Gogna et al., 2022; Igual et al., 2022). Their capacity for sustainable production using non-arable land, minimal freshwater requirements, and potential valorisation of waste streams positions them favourably within circular economy frameworks increasingly prioritised for future food systems.

However, several considerations require attention before widespread implementation. The study utilised standardised in vitro digestion protocols, which, while valuable for comparative assessment, may underestimate bioaccessibility due to fixed enzyme ratios and lack dynamic physiological conditions (Brodkorb et al., 2019). Progression to ex vivo and in vivo studies remains essential for validating intestinal absorption and systemic bioavailability. Clinical trials investigating microalgal iron supplementation in anaemic populations have shown promising results (Leal-Esteban et al., 2021; Othoo et al., 2021), though larger-scale, long-term studies are required to establish efficacy, optimal dosing regimens, and potential adverse effects. Additionally, organoleptic properties, processing stability, and formulation strategies warrant investigation to facilitate consumer acceptance and practical food industry applications.

Regulatory status and novel food considerations

While A. platensis and C. vulgaris benefit from established safety histories and widespread commercial availability, Galdieria sulphuraria occupies a more complex regulatory position within the European Union. The dried biomass of G. sulphuraria was formally submitted in 2019 to EU authorities for authorisation under Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 – the Novel Food regulation – specifically under the category of ‘food consisting of, isolated from or produced from micro-organisms, fungi or algae’. Critically, the species has not been granted Qualified Presumption of Safety (QPS) status, necessitating a comprehensive novel-food dossier and rigorous safety assessment by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA).

As of the latest publicly available information, this application remains pending evaluation, meaning that G. sulphuraria cannot yet be legally introduced as a food or food supplement ingredient within EU markets. Only upon EFSA issuing a positive safety opinion and the European Commission subsequently including the species in the official Union list of authorised novel foods will its commercial use become permissible under EU law. Our Wiise benefit company supports research consortia and enterprises in in preparing and advancing novel food applications. Notably, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Galdieria extract blue as a colour additive in May 2025, demonstrating regulatory progress in other jurisdictions and potentially informing the European assessment process through comparative safety data.

Conclusions and future directions

This comprehensive investigation by ETH Zurich demonstrates that strategic manipulation of cultivation conditions and medium composition enables substantial enhancement of both iron bioaccumulation and bioaccessibility in commercial microalgal species. The research establishes that autotrophic cultivation generally promotes higher iron content, whilst heterotrophic modes enhance bioaccessibility, presenting opportunities for tailored production strategies based on specific nutritional objectives (Gao et al., 2025). G. sulphuraria emerges as particularly promising, combining tolerance to extreme iron enrichment with maintenance of substantial absolute bioaccessible iron content, considerably exceeding conventional food sources.

Future research should prioritise elucidating the molecular mechanisms governing iron uptake, storage, and release in microalgae. Characterisation of iron speciation within cells – including potential heme compounds, ferritin-like proteins, and polyphosphate complexes (Gao et al., 2018; Lithi et al., 2024) – will inform strategies for enhancing bioaccessibility. Investigation of absorption enhancers and inhibitors endogenous to microalgal biomass, including ascorbic acid, polyphenols, and phytate, could guide processing interventions or strain selection for optimised nutritional profiles. Ultimately, the development of standardised microalgal iron supplements and fortified food products requires interdisciplinary collaboration spanning algal biotechnology, food science, and clinical nutrition to translate these promising findings into tangible public health benefits for the billions affected by iron deficiency globally.

Dario Dongo

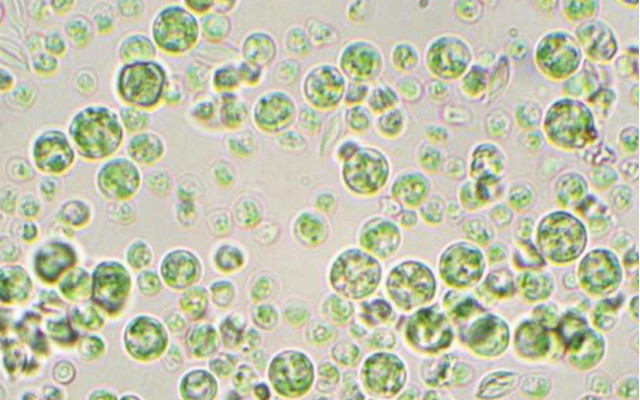

Cover Image: Julia Van Etten (2020). Red Algal Extremophiles: Novel Genes and Paradigms. Microscopy Roday. Doi 10.1017/S1551929520001534

References

- Bermejo, P., Piñero, E., & Villar, Á. M. (2008). Iron-chelating ability and antioxidant properties of phycocyanin isolated from a protean extract of Spirulina platensis. Food Chemistry, 110(2), 436–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.02.021

- Brodkorb, A., Egger, L., Alminger, M., Alvito, P., Assunção, R., Ballance, S., Bohn, T., Bourlieu-Lacanal, C., Boutrou, R., Carrière, F., Clemente, A., Corredig, M., Dupont, D., Dufour, C., Edwards, C., Golding, M., Karakaya, S., Kirkhus, B., Le Feunteun, S., … Recio, I. (2019). INFOGEST static in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal food digestion. Nature Protocols, 14(4), 991–1014. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-018-0119-1

- Canelli, G., Abiusi, F., Garz Vidal, A., Canziani, S., & Mathys, A. (2023). Amino acid profile and protein bioaccessibility of two Galdieria sulphuraria strains cultivated autotrophically and mixotrophically in pilot-scale photobioreactors. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, 84, Article 103287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifset.2023.103287

- Canelli, G., Murciano Martínez, P., Austin, S., Ambühl, M. E., Dionisi, F., Bolten, C. J., Carpine, R., Neutsch, L., & Mathys, A. (2021). Biochemical and morphological characterization of heterotrophic Crypthecodinium cohnii and Chlorella vulgaris cell walls. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 69(8), 2226–2235. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.0c05032

- Gao, F., Lamprecht, N., Stern, U., Abiusi, F., Zeder, C., von Meyenn, F., & Mathys, A. (2025). Iron bioaccessibility assessment and bioaccumulation enrichment in microalgae under different production conditions. Bioresource Technology, 441, Article 133567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2025.133567

- Gao, F., Wu, H., Zeng, M., Huang, M., & Feng, G. (2018). Overproduction, purification, and characterization of nanosized polyphosphate bodies from Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Microbial Cell Factories, 17(1), Article 87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-018-0870-6

- Gogna, S., Kaur, J., Sharma, K., Prasad, R., Singh, J., Bhadariya, V., Kumar, P., & Jarial, S. (2022). Spirulina—an edible cyanobacterium with potential therapeutic health benefits and toxicological consequences. Journal of the American Nutrition Association, 42(6), 559–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/27697061.2022.2103852

- Igual, M., Uribe-Wandurraga, Z. N., García-Segovia, P., & Martínez-Monzó, J. (2022). Microalgae-enriched breadsticks: Analysis for vitamin C, carotenoids, and chlorophyll a. Food Science and Technology International, 28(1), 26–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1082013221990252

- Isani, G., Ferlizza, E., Bertocchi, M., Dalmonte, T., Menotta, S., Fedrizzi, G., & Andreani, G. (2022a). Iron content, iron speciation and phycocyanin in commercial samples of Arthrospira spp. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(22), Article 13949. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232213949

- Kougia, E., Ioannou, E., Roussis, V., Tzovenis, I., Chentir, I., & Markou, G. (2023). Iron (Fe) biofortification of Arthrospira platensis: Effects on growth, biochemical composition and in vitro iron bioaccessibility. Algal Research, 70, Article 103016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2023.103016

- Leal-Esteban, L. C., Nogueira, R. C., Veauvy, M., Mascarenhas, B., Mhatre, M., Menon, S., Graz, B., & von der Weid, D. (2021). Spirulina supplementation: A double-blind, randomized, comparative study in young anemic Indian women. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 12, Article 100884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2021.100884

- Lithi, U. J., Laird, D. W., Ghassemifar, R., Wilton, S. D., & Moheimani, N. R. (2024). Microalgae as a source of bioavailable heme. Algal Research, 77, Article 103363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2023.103363

- Othoo, D. A., Ochola, S., Kuria, E., & Kimiywe, J. (2021). Impact of Spirulina corn soy blend on iron deficient children aged 6–23 months in Ndhiwa Sub-County Kenya: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Nutrition, 7(1), Article 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-021-00472-w

- Paganini, D., & Zimmermann, M. B. (2017). The effects of iron fortification and supplementation on the gut microbiome and diarrhea in infants and children: A review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 106(Suppl. 6), 1688S–1693S. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.117.156067

- Yin, L., Zhang, Y., Wu, H., Wang, Z., Dai, Y., Zhou, J., Liu, X., Dong, M., & Xia, X. (2020). Improvement of the phenolic content, antioxidant activity, and nutritional quality of tofu fermented with Actinomucor elegans. LWT, 133, Article 110087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110087

Dario Dongo, lawyer and journalist, PhD in international food law, founder of WIISE (FARE - GIFT - Food Times) and Égalité.