Vegetarian and Vegan, One None and One Hundred Thousand. The labels of products so marked remain in search of identity. A reflection and a proposal, to supply chain operators and policy-makers.

Thousands of new foods have rained on the market in recent years, thanks to the tremendous growth of the vegan and vegetarian category. The serving component and the concept of healthfulness, moreover, have extended the consumption of plant-based ready meals to even the most hardened carnivores.

The identity of foods presented as vegetarian or vegan, however, is enigmatic in several cases. Linear meters of supermarket shelves are crowded with products whose names are often limited to the evocation of a corresponding meat food, with the addition of the ‘magic little word’. Not enough.

A vegan burger, for example, can in some cases offer significant amounts of protein, carbohydrates, and fat. In other cases, only a modest amount of sugar and plant fiber. The biological value of proteins can vary considerably because of their sources (e.g., soy, wheat) and combinations (e.g., grains plus legumes) to supplement the intake of essential amino acids.

Fancy names such as burgers, nuggets, and veggie patties are therefore completely meaningless, outside of the news of the absence of meat or ingredients of animal origin. In order to tell whether it is a dish or a side dish, the consumer is thus forced to turn each package upside down. Consult the ingredient list and nutritional table in the hope of coming to terms with it.

The name of the food should be displayed on the front of the label and especially coded. A requirement should be established to specify, next to the name, the primary ingredient (e.g., ‘grain and chickpea preparation,’ or ‘vegetable-based’). Only in this way-precisely because these are novel foods-can consumers easily identify those that match their dietary and meal composition needs. (1)

The terms ‘vegan’, ‘vegetarian’ or similar must also be regulated uniformly in the EU Internal Market. In accordance with the European Vegetarian Union‘s Guidelines, which respond to common feeling shines in clarity. The use of such wording must obviously be matched by scrupulous compliance with the relevant requirements, to which must be added the obligation of so-called internal traceability. (2)

The Vegetarian and Vegan symbols must also be standardized at the European level, as is already the case for organic products. For the specific purpose of making it easier for vegetarian and vegan consumers to purchase foods of various kinds. Saving them from the need to study ingredient lists that are sometimes enigmatic ‘by law,’ (3) from the standpoint of compatibility with such diets.

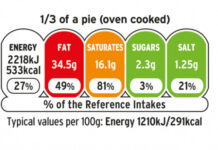

Traffic light labels are also indispensable on ‘novel foods’ for vegetarians and vegans. All the more so since such products today meet an expectation-sometimes unfounded, (4) and yet legitimate-of ‘healthy choice.’ Instead, this is often not the case, as we showed in a recent market survey revealing salt levels that are far in excess of WHO recommendations.

Good practices and new rules, for the best protection of consumAtors.

Dario Dongo

Notes

(1) Outside of traditional macrobiotic preparations such as tofu, seitan, tempeh. And of traditional seasonings, such as tamari, shoyu, gomasio, umeboshi

(2) That is to say, in order to label a food as vegan or vegetarian, the responsible operator will have to ensure that all ingredients, additives and processing aids used in its processing are fully registered. In addition to the segregation of production cycles (as opposed to those in which animal-derived ingredients are used instead), that is, the sanitization of premises and equipment

(3) As is the case with food gelatin, typically made from pig and cattle carcasses. Of mono- and diglycerides of fatty acids, which can be cited as such when also of animal origin. And of various additives

(4) Too many products have been rushed to market, imposed by marketing, that often did not allow R&D departments to develop processes without employing additives go-go. Neither calibrate the nutritional profiles of products

Dario Dongo, lawyer and journalist, PhD in international food law, founder of WIISE (FARE - GIFT - Food Times) and Égalité.